Anti-Creativity: Creating Destruction

The Dark Side of Creativity: Part 4

Hi,

This is the fourth part of my series on the dark side of creativity. You can read them all at Everyone’s Creative.

Making things that unmake things.

When I talk about creativity, I’m being very literal about the word. Creativity is our capacity to create things: art, engineering, relationships, ideas, etc. I’m deliberately being broad with this definition because I think narrowing the definition of creativity only serves to increase gatekeeping and isolate us from one another.

But there is one line I constantly want to draw, and that’s between things we create which are a net-gain in overall creation, and the things we create which destroy. Things that we create that ultimately take away more than they add feel very different from any other forms of creativity, and yet I’m not willing to label them as something else entirely. They’re still acts of creativity.

The most simple and blunt example of this is the atomic bomb. The atomic bomb is inarguably a significant effort of human creativity. The creation of that weapon took the collaboration of hundreds of extremely smart people, working in different fields and coming together to create something that had never existed before. It pushed the boundaries of our understanding of physics, engineering and changed the course of geo-politics forever.

It also killed an unimaginable number of civilians, destroyed cities and left generations of trauma and fallout in its wake. So, was the creation of the nuclear bomb a net-gain of creation or a loss?

This is a pretty morbid and inhuman question to ask. I don’t think a reasonable person can entertain the idea that there is something positive about the detonation of two nuclear bombs in Japan that ultimately made it worth the cost. It was a horrifying decision and the acts of creativity that led to the bomb’s creation are ultimately a loss for humanity. It was anti-creativity, but still a form of creativity that we need to reckon with.

This idea will largely make the most sense with the discussion of weapons and tools of modern warfare. We’ve reached a creative capacity to make things so unimaginably efficient at killing people and destroying things that any argument for their usefulness outside of these horrors is absurd. I wouldn’t necessarily say the the creation of the first bow and arrow is the same, but remote operated drones and increasingly efficient automatic rifles feel like another net-loss for humanity in terms of our capacity to create. And yet, making these things still requires creativity. It requires intelligence, planning, brilliant minds and a creative will to make something exist that didn’t exist before. That’s a capacity that all of us carry with us into the world. These are things that people (people just like you) create.

But this isn’t just about weaponry and war. Humans have used our capacity for creativity to come up with less tangible tools that have destroyed less obvious parts of our world. The creation of the factory and the ideas behind Taylorism led to the destruction of cottage industries, the destruction of lives through child labour, and increased the suffering of working people in ways we still feel to this day. The creation of social media and 24-hour news have obviously destroyed our social cohesion, eroded trust in media and wreaked havoc on our grasp of the truth. The creation of the internal combustion engine and refined petroleum products are leading directly to the destruction of our very planet (at least, the version of our planet that is habitable to us).

The problem with this concept of anti-creativity is that if you let it fill your mind too deeply you can start to see it everywhere. As you follow this train of thought, you can get caught in a retroactive cost-benefit calculation going back to the invention of the first tools and the beginning of human society. Was it all just a big mistake? Would we be better off if we had never made anything at all?

But all of that misses the point. I don’t think there’s value in trying to point a finger at one particular creative act to discover the catalyst of all of the world’s problems. My point with this idea of anti-creativity is to challenge us all to be more careful in how we think about creativity and making things. I’ve discussed this before, but I think creativity is one of the most powerful aspects of being human, and that means it’s our job to be sure we use that power responsibly (thanks, Uncle Ben!). The most dangerous thing you can do is pretend that creativity is somehow neutral or that the act of creating something can be separated from the impact that thing has on the world. We’re all responsible for our creativity and what we do with it, and we should try to make sure that we at least don’t make the world worse with the things we make.

People always come before things. That’s how I justify some acts of destruction being outside of this definition of anti-creativity. The artist Ai Weiwei famously photographed himself destroying a “priceless” Han Dynasty urn, similarly “ruining” others by dipping them in bright paint and putting them on display in art galleries. To some, this was a selfish and horrific act of vandalism, but to me it is a sensitive way of pointing out how easily we value objects over people. In a way, it’s a performance of the exact boundary I’m trying to find between creativity and anti-creativity.

Another artist would go on to smash one of Ai Weiwei’s painted vases in one of the galleries displaying the work as an act of protest about international artists getting favoured over local artists in these establishment spaces. He was arrested. Ai Weiwei’s destruction was creative enough for the gallery to approve of but this artist’s destruction was a crime.

Somewhat hilariously, about this artist’s protest, Ai Weiwei said “You cannot stand in front of a classical painting and kill somebody and say that you are inspired by [the artist].” To me, even Ai doesn’t seem to see destruction as a medium of creation here, instead seeing it as the subject matter. But that doesn’t really track, does it? Caravaggio didn’t have to behead someone in order to depict Salome with the Head of John the Baptist, but Ai Weiwei did have to destroy a vase in order to photograph its destruction. This seems like a double standard to me. I think both artists smashing vases were painting with the same brush of destruction, even if each performance had a different impact.

So how do we measure if an act of destruction creates enough value to be permissible? I know the atomic bomb went too far and that Duchamp’s waste of a urinal is fine. I guess the answer is somewhere in between the two.

The brightest part of the line always has to do with other people. Your creativity only exists in relation to others, even if it is in spite of them, and so I can’t abide by creative acts that actually harm other people. The kind of abuse that people like Stanley Kubrick put his actors through in order to make “masterpieces” is, to me, not worth the finished result and we’d be better off as a culture with a less intense performance from an untraumatized actor.

But the destruction of objects, property or ideas feel fair game. Ai Weiwei’s destruction transforms symbols and objects rather than removing them from the world. The same way that making paper for a drawing destroys trees, there is always going to be some cycle of consumption and destruction going on when we make things, but we should try to aim to be intentional or at least considerate of that cost as a part of what goes into our creative acts.

The world is feeling particularly destructive at the moment. We’re witnessing in real-time as some world leaders argue that the world they are trying to create is worth the amount of suffering and destruction it will take to bring into fruition. For Israel, the destruction of an entire people seems to be worth it to create their vision of what the world should be. For the U.S. Republican party, the destruction of American democracy seems to be worth it to create their vision of what the world should be. In Canada, our government seems to think creating economic growth and increased national “security” is worth destroying the environment and our civil rights. At one time, the creation of the atomic bomb and the destruction it would create was deemed worth it to win a war.

What do you think? Are these positive creative pursuits? Are these things worth making?

Anti-creativity isn’t separate from creativity. It is just another way of being creative. It’s all on the same spectrum of our human capacity to do things with our ideas and manifest them in the world. Once you accept this, you realize how responsible we all are for the things we create and how no act of creativity is neutral. I don’t know about you, but I want to make things that make the world better, or at least not actively worse.

Love,

Simon 🐒

🔗 Links & Thinks 🧠

You know that the world is kind of fucked right now. I don’t need to link you to a bunch of news about that. I do think it’s worth engaging in the real world, though. Check in on people close to you. Do things to help out where you can. Also, do some things that you enjoy and remind yourself that two opposites can exist at once and that this world is awful but also wonderful and worth living in. Make something that makes the world a bit better, even in a small way. Have you looked at the moon recently? It’s fucking amazing!

For my part, I’m still working on getting the hell off of Substack. Abiding the platform that abides Nazis is feeling less and less viable for me and if I want to keep creating Everyone’s Creative then I need to feel like it isn’t contributing to a platform that facilitates harm.

To that end, I’m working on moving Everyone’s Creative over to a much smaller, niche little platform called micro.blog. It’s where I host my personal website and it gives me a lot of flexibility to customize the theme and play with the back-end of the site to make something exactly the way I want it. It’s probably not the best platform for most people moving off of Substack, but it’s cheaper than Ghost and more customizable than Buttondown and, frankly, I’ve just really been having fun learning more about Hugo, HTML and CSS to get things set up there.

You can see the work-in-progress site at ec-test.micro.blog and, if you’re interested, the theme can be found on my Github. My short-term goal is to have that site ready enough in the near-term to move over to entirely. For my 90 or so existing email subscribers, you won’t need to do anything to follow me there. I’ll let you know once I’m making the shift and you’ll still receive Everyone’s Creative in your inbox whenever I publish. For any Substack followers, I’ll still share links to new posts through Substack Notes, but I’ll probably engage with Substack a lot less (that’s the goal, at least).

You can still subscribe here and come along with me to Everyone’s Creative’s new home when it's ready.

If you publish on Substack, I’d encourage you to look into alternatives that fit your needs but also know that I don’t really believe being on a platform equates to supporting everything it does. Your voice still matters, though, and you can let Substack, Substack Team, Hamish McKenzie, Chris Best and Jairaj Sethi know that Nazis are fucking lame by telling them directly. Substack has a lot of VC debt and needs to figure out how to make money, so telling them that being chill about Nazis is making you want to leave may make them reconsider things.

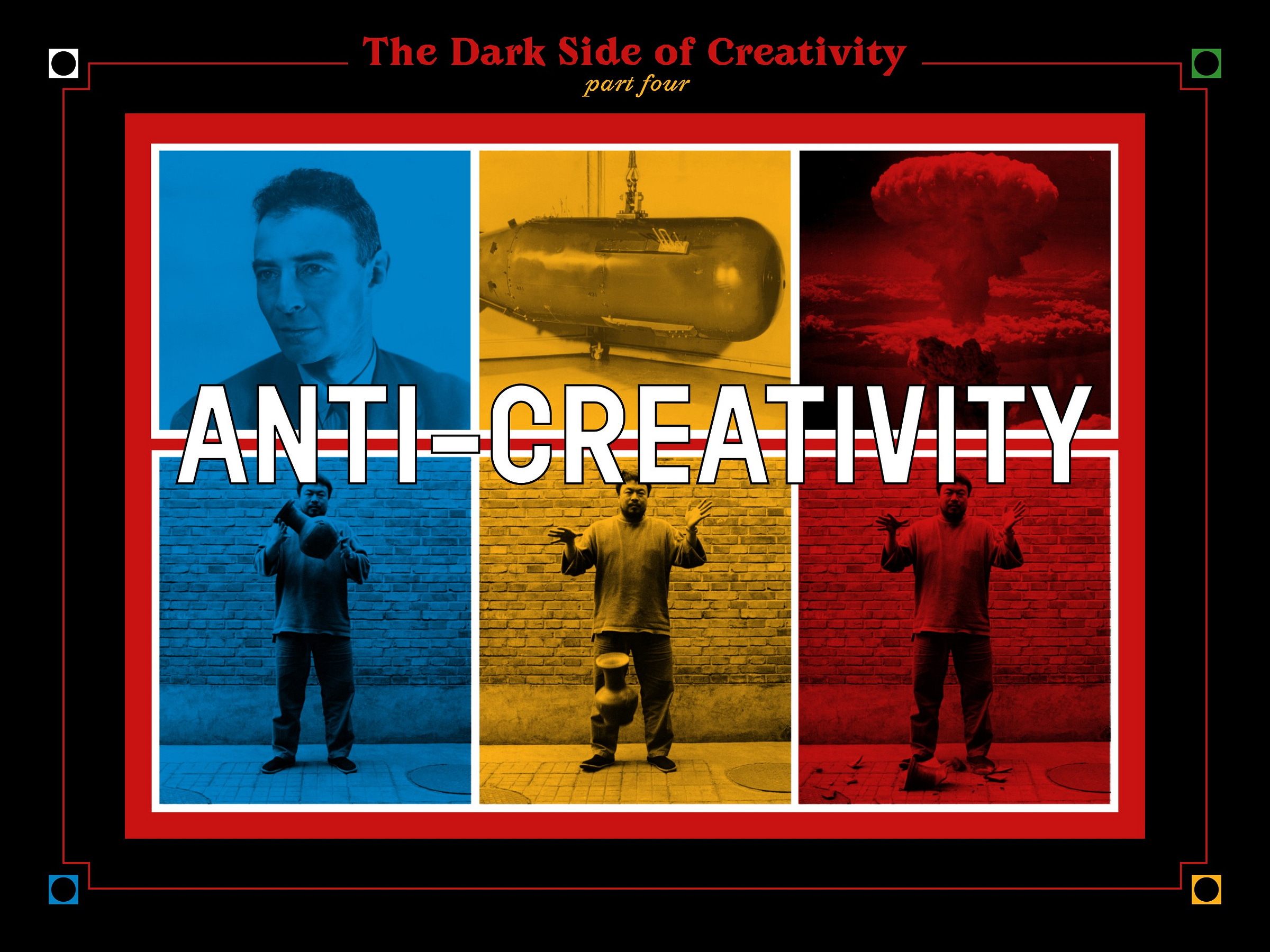

The banner image for this post uses six photos.

The bottom three of them are the photos from Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn by Ai Weiwei.

The top-left image is of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

The top-centre image is of a “Little Boy” atomic bomb.

The final image, top right, is of the mushroom cloud above Nagasaki after an atomic bomb was dropped by the United States on August 9, 1945. It’s estimated that 60,000 people were killed by that bomb and, combined with Hiroshima, “the bombings killed between 150,000 and 246,000 people, most of whom were civilians.”