Picking an idea, self-plagiarism and figuring out how to start

After my last post about remembering how to come up with ideas, I was left with another conundrum to navigate: actually choosing an idea to start developing into a game.

Choosing my idea ended up being about finding something that felt like it had legs. Something that I thought had a lot of different possibilities, even if I couldn’t quite see all the possibilities yet. It felt a bit like staring at a bunch of puddles, and trying to figure out which one was the deepest by only looking at them.

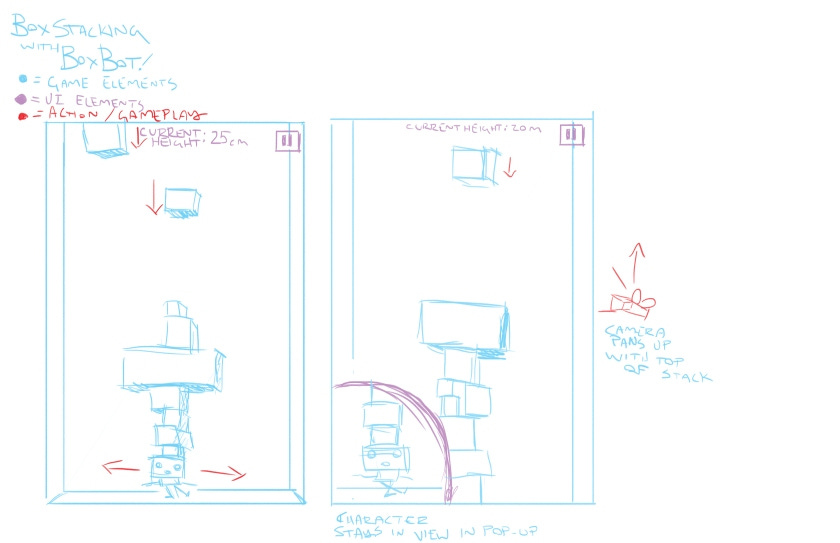

I shared the above sketch previously of an idea I was playing around with about a year ago when I started thinking of making a game. I was calling this game BOXBOT, and my idea for it was to make a very simple game where you move a character back and forth and catch boxes on your head as they fall from the sky. The main mechanic would be around trying to maintain your balance as the tower became taller and taller. It was a direct rip off of a mini-game from the Nintendo Wii game, WarioWare: Smooth Moves. I literally thought to myself, “I should make a game like that game”. I kind of thought it would be easy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8je0uRaIg2c

BOXBOT never felt like an idea with depth. I felt like I could see all that the idea had to offer before I even started. In a way, that might have been good – like having an idea for a painting that you can see vividly in your mind before you start painting – I sometimes think having a vision and inspiration for something can be a good place to start. In this case, though, I could see that game clearly in my mind and it just didn’t excite me, which is part of why I think I never pursued it further.

In another way, I think having an idea that isn’t so clear in your mind can actually be a more exciting artistic endeavour. The feeling of experimentation, exploration and discovery you can have from figuring out what that work is, is in a lot of ways the very ethos of what I want this project to be about. It’s about learning and uncovering things I didn’t think I could do. For that reason, I feel like my idea should be something I discover as I work on it.

After exploring a few different ideas, I eventually came back to BOXBOT, because something about the character and the wrapping of that idea felt like it had potential – it was just the game part that I didn’t love. That’s where Andy J. Pizza’s idea about plagiarizing yourself came into play for me, and everything seemed to come together. Essentially, his idea is to look to your own past work and to pull from those ideas in the future when you’re trying to find something to work on now – refining your own ideas from the past by plagiarizing yourself in the present.

Several years ago, I wrote and drew a four-page comic about a strange little creature that lives in a cardboard box, loves boxes, and collects them in their box house with a disturbing, fetishistic obsession. At the time, it felt a bit like a throw-away idea, but I’ve always been really fond of the character and the “box collector” idea. I think the idea is partly drawn from my own instinct for hoarding boxes from every computer, iPod and game system I’ve ever bought – something I’ve been working very hard to get over in recent years.

So that’s where everything clicked, thematically, and I found the narrative for my game: you play as a box-collecting robot (made out of a cardboard box) designed by an obsessive box-collector to go out into the world and find more boxes for them to hoard.

Once I’d convinced myself about the direction of my idea for the story and justification for this game, I started to rework my idea for the gameplay mechanics. The falling and balancing boxes idea from earlier was clearly not interesting enough, but I started to think of an idea where you’d stack boxes on your head and try to balance them as you navigate through an obstacle course. Something like one of those egg-and-spoon races, except you’re trying to balance three eggs on top of eachother at once.

In the end, I realized the idea of building a physics-based game wasn’t the direction I actually wanted to go. I’m not really interested in writing my own physics engine (and I’m quite sure that that is outside of my ability, too), and so building a game around manipulating physics to keep something in balance wasn’t the direction I wanted to take. But the idea of stacking these boxes on top of your head was still interesting to me.

In the end, the idea I came up with was solidified when I made this paper prototype of a super simple level to justify an idea to myself.

In the game, you’ll be presented with a level and a series of boxes you have to collect before you can exit. But, unlike other games where, when you pick up a collectible, it gets added to an inventory and effectively stops existing in the world, in this game, when you pick up a box it will get stacked on top of your head. This means that as you collect the objective boxes in each level, the size, shape and weight of the player character will start to change. What I came up with in my super simple paper prototype was a level where, if you pick up the boxes from left to right, you won’t be able to fit in the last area to pick up the final box. So, instead, you have to pick up the boxes from right to left to be able to exit.

This idea is what I’m talking about when I say I want an idea that I can feel has depth, even if I can’t see everything yet. To me, the different ways that picking up the boxes will affect how you can navigate the level feels like something I can iterate on endlessly to create a lot of interesting little puzzle rooms for players to figure out.

And so, that new gameplay idea, paired with a solid feeling narrative concept, led me to feeling ready to start prototyping. And that’s where I hit my next roadblock: how do you actually start making a game?

Blog appendix: taking time away from this project

When I announced that I wanted to make a game, I deliberately avoided committing to a cadence for these blog posts. Part of that was because I was already committing to one big project (making a game) and committing to another felt like I might be biting off more than I could chew. Another reason, though, is that I already have had plenty of professional experience that told me that sticking to that kind of schedule would only do one thing: create a lot of artificial stress for myself.

I love deadlines. They are, in a lot of ways, the only thing that truly motivates me to get anything done. But with longer term projects – especially ones that are meant to be done in your “spare” time – I find that setting arbitrary deadlines for yourself can create a lot of self-imposed stress, and they rarely account for the unpredictability of life.

And so, even though in my mind I had softly committed to weekly blog posts, I ended up skipping a couple weeks because other work, family emergencies, my own mental health and less dramatic things like relaxing and spending time with my partner all took precedence over this project.

And here’s the thing: I don’t think any of that is bad, and I don’t believe that mentality will prevent me from finishing this game.

One of the many harmful rhetorics that is perpetuated by basically everyone, whether they realize it or not, is that you have to sacrifice everything if you want to be successful. Your friends, family, personal life and health – all of those need to come second to your work if you want to make a splash in the world. To me, that feels wrong, and it certainly doesn’t seem worth it.

And so, if I’m going to commit to anything with this project, it will be that it will not become a source of negativity in my life, and I’ll continue to make space for everything else if this work starts to get in the way.